When Prince Albert married Queen Victoria on this day in 1840, she famously wore a brooch that he had given her the night before. After the ceremony, more special brooches were given by the couple to their twelve bridesmaids: striking turquoise baubles in the shape of heraldic eagles.

Queen Victoria was twenty years old, and had already been monarch for almost three years, when she married her 20-year-old first cousin, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, in London on February 10, 1840. Victoria had fallen deeply in love with Albert, who returned her feelings to such a degree that he accepted her marriage proposal in October 1839.

Victoria and Albert’s marriage is still the most recent wedding of a reigning British monarch. All others, with the exception of Edward VIII, were married when they ascended to the throne. Victoria’s nuptials, therefore, were particularly important. She was selecting not only a spouse but someone who would act almost as a co-head of state, as well as the parent of the next monarch in the family line.

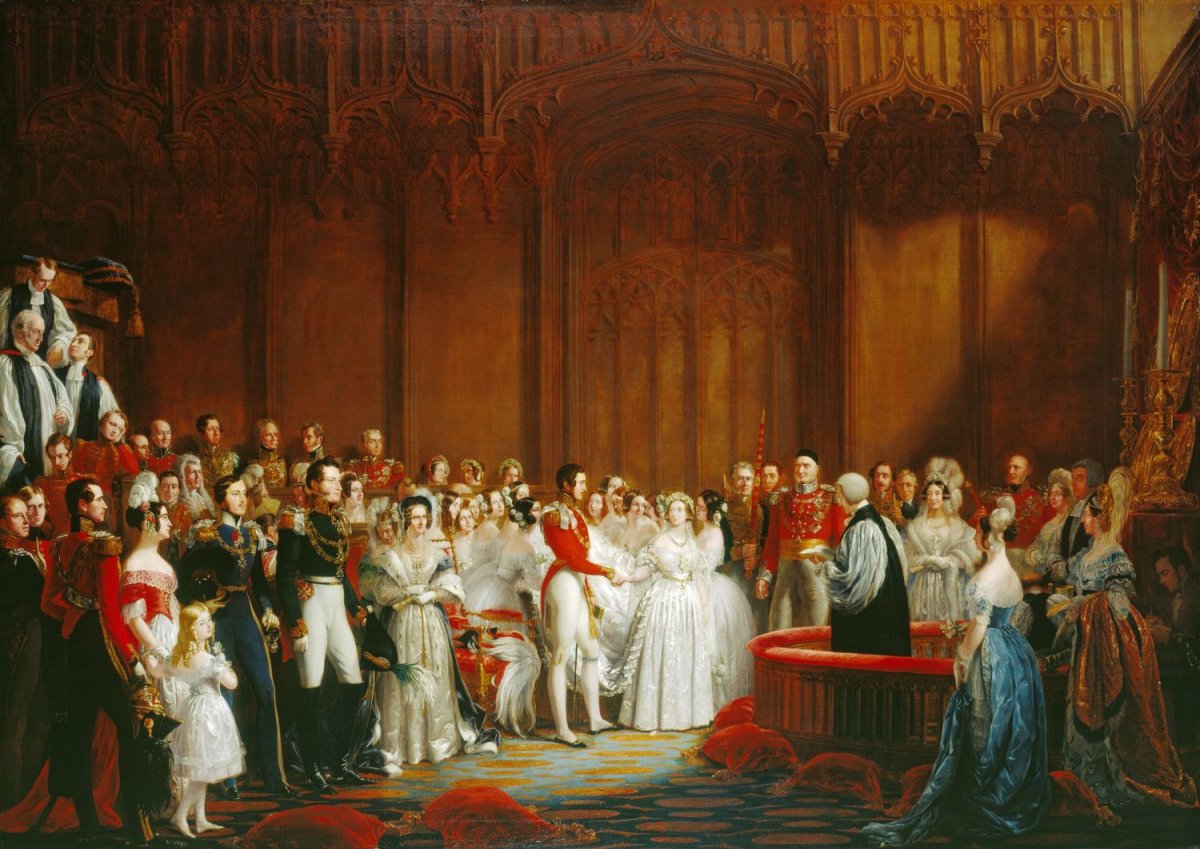

The couple’s marriage was solemnized at the Chapel Royal, St. James’s Palace in London. Victoria arrived for the ceremony wearing a white dress of satin and lace, with all of the material patriotically produced in Britain. The ensemble was magnificently adorned with jewels, including diamonds that she had been given by the Sultan of Turkey and the diamond and sapphire cluster brooch that Albert had given her on the night before the wedding.

The entire look culminated in a long train: eighteen feet of satin and orange blossoms, handled by a group of twelve aristocratic bridesmaids. They followed Victoria in pairs, one on each side of the train, wearing simple white dresses trimmed with sprays of roses. Additional roses were nestled in their hair as well. Queen Victoria herself had dreamed up the design for the dresses. The gowns were then made under the supervision of the Mistress of the Robes, the Duchess of Sutherland, whose sister, Lady Elizabeth Howard, was one of the bridesmaids.

The young women who served as bridesmaids were all the unmarried daughters of aristocrats. Five of them—Lady Caroline Gordon-Lennox, daughter of the 5th Duke of Richmond; Lady Adelaide Paget, daughter of the 1st Marquess of Anglesey; Lady Wilhelmina Stanhope, daughter of the 4th Earl Stanhope; Lady Frances Cowper, daughter of the 5th Earl Cowper; and Lady Mary Grimston, daughter of the 1st Earl of Verulam—had already had experience shepherding Victoria’s regal garments when they served as Maids of Honour during her coronation two years earlier.

They were joined by seven more young women for the wedding: Lady Mary Howard, daughter of the Earl of Surrey; Lady Eleanora Paget, daughter of the Earl of Uxbridge; Lady Sarah Villiers, daughter of the 5th Earl of Jersey; Lady Elizabeth Sackville-West, daughter of the 5th Earl De La Warr; Lady Jane Pleydell-Bouverie, daughter of the 3rd Earl of Radnor; and Lady Elizabeth Howard, daughter of the 6th Earl of Carlisle. The twelfth and final bridesmaid was also one of Queen Victoria’s cousins. She was Lady Ida Hay, the eldest daughter of the 18th Earl of Erroll. Lady Ida’s mother was Lady Elizabeth FitzClarence, who was the sixth child of King William IV, then Duke of Clarence, and his mistress, Dorothea Jordan.

The bridesmaids at Victoria and Albert’s wedding had a slightly more difficult job than anticipated. Because the train was eighteen feet long, and there were twelve young women carrying it, they were scrunched together tightly as they maneuvered the dress down the aisle of the chapel. Short, quick steps replaced longer, more elegant strides as they followed the monarch.

Their efforts were richly rewarded. After the wedding ceremony, Victoria and Albert gathered all twelve of the bridesmaids together in a private room at the palace, where a table had been placed. As they waited, a member of the palace staff brought out a plain cloth bag and handed it to the Queen. Inside the bag were twelve small blue velvet boxes.

Inside each box was a silver brooch shaped like an eagle, an important German heraldic symbol. The birds were studded with turquoises, with diamonds used to represent the beak and a ruby set as the bird’s eye. In its golden claws, each eagle clutched a pair of round white pearls. The Royal Collection Trust notes that Victoria herself was very involved with the making of the brooches, especially the gemstones chosen for the pieces: “The stones used were all highly symbolic: turquoises and pearls representing true love, rubies for passion and diamonds for eternity.”

The brooches had been made by a London jeweler, Charles du Vé, who had a workshop in Maddox Street and sometimes did work for Garrard, then the crown jeweler. The bridesmaids, many of whom made glittering aristocratic matches of their own, treasured the gifts. Some of the families still own the turquoise eagle brooches given to their ancestors, while others have passed into other hands. The present Duke of Bedford, for example, apparently still owns the brooch given to Lady Elizabeth Sackville-West, who later married the 9th Duke of Bedford.

In Ancestral Jewels, the late Diana Scarisbrick features a portrait of the Duchess of Bedford wearing her brooch, and Scarisbrick notes that additional bridesmaid brooches survive in the family collections of the Marquess of Salisbury (a descendant of Lady Frances Cowper) and the Earl of Gainsborough (a descendant of Lady Ida Hay). Exactly what happened to the nine remaining brooches is unclear. One of them is part of the Royal Collection, having been acquired by Queen Mary in 1925.

Another belonged to Princess Marie Louise of Schleswig-Holstein, who states in her 1957 memoir that she owns “a bird of turquoises” given by Queen Victoria to “her train-bearers” as a souvenir. (Some believe that Marie Louise’s brooch is the same one as the RCT brooch, but if Marie Louise did indeed still have her brooch in 1957, the timing doesn’t seem like it works.)

Yet another example is in the collection at the British Museum. That brooch was lent, and then donated, to the museum by one of its trustees, the Hon. Mary Anna Marten, who was herself a daughter of the 3rd Baron Alington and a granddaughter of the 9th Earl of Shaftesbury. And there’s one more brooch from the original twelve in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. That particular brooch was acquired by the antique jewelry dealer Wartski in 2019 and subsequently sold to the Boston museum.

That means that a total of six brooches appear to be accounted for: the Bedford brooch, the Salisbury brooch, the Gainsborough brooch, all in private collections; and the Royal Collection brooch, the British Museum brooch, and the MFA Boston brooch. Here’s hoping even more will wing their way into the public eye in years to come.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.